Post 13. Iraq’s 1990 Invasion of Kuwait

The glorious tale has been told and retold. On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded and annexed its oil-rich neighbor, Kuwait. Just over four months later, on January 16, 1991, a U.S.-led multi-national coalition launched a massive assault, Desert Storm, first from the air, pummeling Iraqi infrastructure and air defenses for more than a month, and then on February 24, unleashing a lightning ground war that in just 100 hours sent what was left of Saddam’s forces fleeing back to Bagdad on the “highway of death.” Liberating tiny Kuwait from big bad bully Saddam Hussein. Shock and awe. Might and right. Glorious.

Not so glorious, the back story, why Saddam invaded Kuwait and thought he could get away with it because of what the U.S. said and did not say. Interesting for historians, you might say, but what difference does it make now? After all, almost 30 years have passed, even the 2003 war on Iraq was 17 years ago and Saddam is long dead.

It matters because, in our own version of “ground hog day,” we continue to make the same mistakes again and again, choosing expediency over principles, being impulsive when we should be patient, timid when we should be bold, and most of all not saying what we mean and meaning what we say. The consequences are often catastrophic. Perhaps, instead of always trying to justify our mistakes – Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait is just one example – we might try learning from them.

_____________________________________________________________________

In 1988, at the end of his disastrous 8-year war with Iran, Saddam Hussein was in a financial and political box. Iraq’s oil-production facilities and ports were in shambles, and he could not rebuild Iraq’s devastated economy with crude oil under $20/barrel. The Ayatollah Khomeini continued to incite Shi’a Muslims in southern Iraq – Shi’a make of 60% of the Iraqi population – to overthrow him, and the fractious Kurds of northern Iraq were intent on breaking away to form their own independent country. And most worrying, Saddam could no longer depend on unquestioned loyalty from his officer corps.

Having himself come to power in a coup, Saddam had good reason to be paranoid about his own survival, and after ruthlessly eliminating so many of his opponents, real and imagined, he had no illusions about his fate if deposed. So he did what endangered politicians always do, he found a scapegoat. Kuwait.

Iraq had borrowed almost $40 Billion from Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia to finance its war with Iran. Saddam argued that these loans should not be considered “debts to Iraq’s Sunni Arab brothers,” rather their share of the cost of Iraq protecting them from fundamentalist Shi’a Iran.

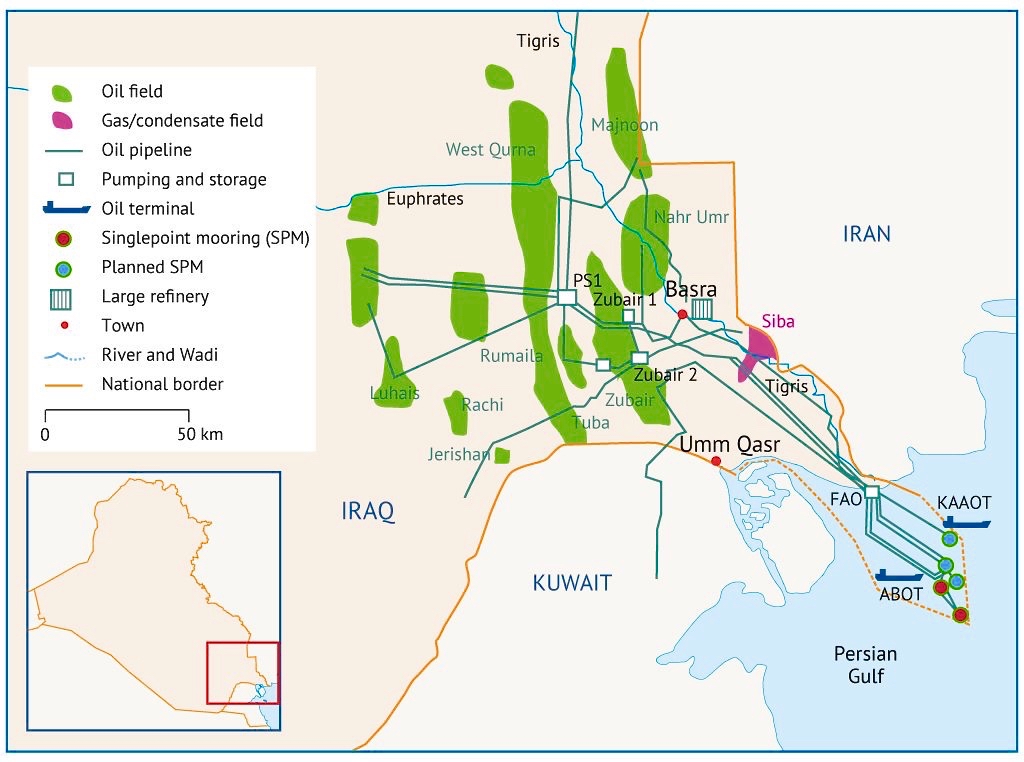

Kuwait and UAE refused. Saddam felt betrayed, and accused them of intentionally weakening Iraq by exceeding their OPEC quotas for oil production, driving the price down to as low as $11/barrel and cutting almost $14 billion a year from Iraq’s oil revenues. He also claimed that Kuwait was slant-drilling, with U.S.-made equipment, into the Iraqi side of the Rumaila oil field, only a small piece of which straddles the border into Kuwait, in short, stealing Iraq’s oil. Saddam called it war, an economic war, but war nonetheless.

In fact, this was only the most recent installment of Iraq’s long-festering resentment of Kuwait, of its very existence, and like so many Middle East conflicts, Iraq’s beef with Kuwait was rooted in British imperialism. Kuwait had long been a part of the Ottoman Empire’s province of Basra in what is now southern Iraq, ruled since 1756 by the al-Sabah dynasty, but in 1889, it became a British protectorate, giving Kuwait autonomy from the Ottomans and, in the bargain, Great Britain and its East India Company a deep-water port on the Persian Gulf.

In 1921, following the breakup of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I, it fell to Sir Percy Cox, High Commissioner for the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, to fix the borders of Iraq, Kuwait.and what was to become Saudi Arabia.

Gertrude Bell, an Oxford-educated writer and archaeologist, and like Cox fluent in Arabic, played a major role as mediator in the formation of Iraq. She has been described as “one of the few representatives of His Majesty’s Government remembered by the Arabs with anything resembling affection.”

Channeling Sykes and Picot, Cox took out his red pencil and blithely carved up an immense swath of the Ottoman Empire.

He gave Iraq a large part of the area claimed by Ibn Sa’ud, whose extended family still rules Saudi Arabia today, and to placate Ibn Sa’ud cut off two-thirds of Kuwaiti territory and put it on the Saudi side.

To make sure that everyone’s camel got gored, he gave Kuwait the lion’s share, 310 miles, of the Persian Gulf coastline, including Bubiyan, Warba and seven other islands, leaving only 36 miles of marshy coast to Iraq.

Ever since, Iraq had claimed that Kuwait was stolen from it by the perfidious British. This became a less academic issue in 1937 when massive oil fields were discovered under Kuwait, which by 1952 became largest oil exporter in the Middle East. Just months after Kuwait became independent in 1961, Iraq sent troops across the border and pumped oil out of its northern fields until prompted to leave by the arrival of a British paratroop brigade.

Twenty years later, early on in the Iraq–Iran War, Kuwait feared for its own survival if Iran prevailed, so it gave Iraq more than $10 billion in loans. But after the war ended, with Basra and Iraq’s oil ports on the Shatt al-Arab waterway blocked by wreckage from the battles with Iran, Saddam pressured the Kuwaitis to sell or lease Bubiyan and Warba, the islands between the Gulf and Iraq’s Umm Qasr and Khor Zubair oil terminals.

Well aware of Iraq’s long-standing claims on Kuwaiti territory, and no doubt fretting that saying yes would only lead to more Iraqi demands, the Emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al-Sabah, said no deal, we will lend you money to fight Iran, but our islands are not for sale or rent.

Iraq’s grievances with Kuwait went on the back burner only until its war with Iran ended. In February 1990, Saddam took his case to the Arab League, demanding, in addition to a moratorium on Kuwait’s loans, that OPEC limit oil production to increase the price over $25/barrel. In the ensuing four months, trying to gauge how far he could press his hand, Saddam upped the ante, demanding that Kuwait sell – later he would say cede – Bubiyan and Warba to Iraq and pay it $30 billion as compensation for OPEC quota violations.

He was, no question, trying to make Kuwait offers it could only refuse, itching for war, hell-bent on taking Kuwait by force and solving all of his problems, or so he thought, in one fell swoop.

By annexing Kuwait, Saddam would control its 310-mile coastline, and double, to 20%, Iraq’s share of global oil reserves. More than anything else, it would send a message to the Saudis and other Sunni neighbors, and especially to Shi’a Iran, that he would not be pushed around, indeed, he would do the pushing.

Besides, Saddam calculated, who would complain? Not the British or French, who were buying oil from Iraq and selling it military hardware. And not the Saudis, Syrians or Egyptians, who despised the Kuwaitis as arrogant little pissants.

In 1990, Egypt’s per capita annual income was less than $500 and Iraq’s less than $2,000, but Kuwait’s was more than $10,000, and it had a sovereign wealth fund of an estimated $100 billion, on top of 10% of the world’s crude oil reserves.

And it was not as if native-born Kuwaitis were industrious: they counted their oil money, scandalized conservative Arabs with their gambling, drinking and prostitutes all over Europe, and left the dirty work to ex-pat Egyptians, Indians, Pakistanis, Filipinos and Palestinians who made up more than 80% of Kuwait’s population. Not a sympathetic bunch, to say the least.

That left the U.S., and Saddam believed that the it did not have the stomach for a bloody war with Iraq, not after Vietnam, and certainly not to rescue the Kuwaitis, who were virulently anti-American and anti-Israel. As Saddam put it to April Glaspie, U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, “If the Iranians had overrun the region, [you] would not have stopped them, except with nuclear weapons, . . . [because] yours is a society which cannot accept 10,000 dead in one battle.”

Moreover, the U.S. had sent many signals to Saddam that he was on a very long tether, if not completely off leash. For starters, the U.S. had given Iraq almost everything it asked for in its war on Iran, which, it is worth emphasizing, Saddam justified as the only way, invading a neighboring country, he had to resolve a border dispute. Did we really think that Saddam would never do that again, or that he thought we would object if he did?

In 1988, after Iraq killed hundreds of Kurds with poison gas, Congress voted to impose economic sanctions on Iraq, but the Reagan administration blocked them, and in January 1990, President George H.W. Bush reaffirmed that the U.S. had “normal relations” with Iraq.

April 12, 1990, five U.S. senators called on Saddam, Bob Dole (R. Kansas), Alan Simpson (R. Wyoming), Frank Murkowski (R. Alaska), James McClure (R. Idaho), and Howard Metzenbaum (D. Ohio), with Dole bearing warm greetings from Bush. Saddam carped at them for an hour about a Voice of America commentary lumping Iraq in with North Korea, Cuba, Iran, etc., as a police state. The senators turned themselves inside out apologizing. Simpson declared, “The [American] press is spoiled and conceited. All journalists consider themselves brilliant political scientists. . . . My advice is . . . allow the bastards to come here and see things for themselves.” The message, in short, “You’re a great guy and we’re on your side.”

In mid-July, the CIA warned that Iraq was massing troops near the Kuwait border and an invasion was “highly likely,” But when Margaret Tutwiler of the U.S. State Department was asked on July 24 if the U.S. would defend Kuwait, she stated, “We do not have any defense treaty . . . or security commitments to Kuwait.”

Next question. “Has the U.S. made any diplomatic protest to Iraq about putting 30,000 troops on its border with Kuwait?” Tutwiler: “No, I am entirely unaware of any such protest.” She added, “We also remain strongly committed to supporting the individual and collective self-defense of our friends in the Gulf with whom we have deep and longstanding ties,” but it is unclear which “friends” she had in mind.

[Ron Sachs / Getty]

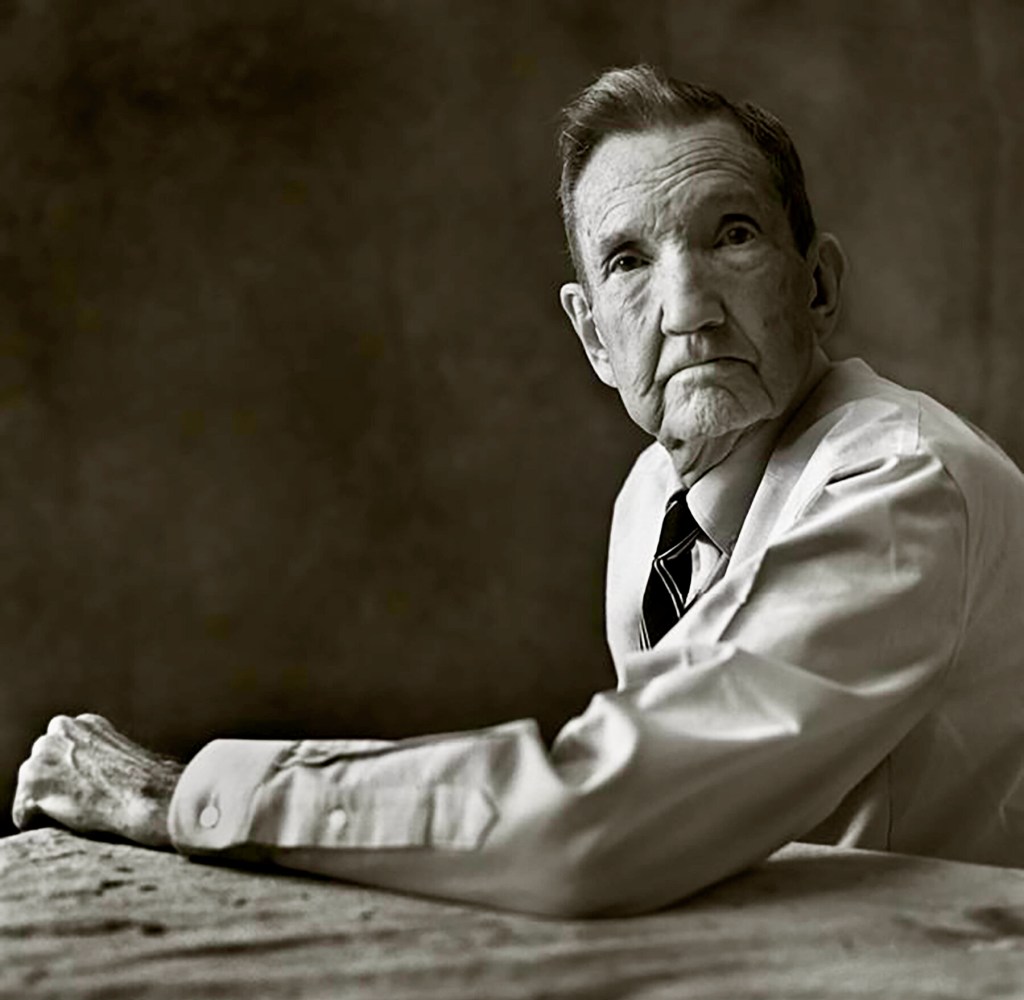

The very next day, July 25, Saddam Hussein summoned April Glaspie, the American ambassador to Iraq. Born in Vancouver, raised in California, Glaspie was a very respected, no-nonsense, career diplomat who “spoke Arabic like a nightingale.”

Being the very first woman ambassador in the Middle East was not a big deal in secular Iraq, but after two years in Bagdad she had never even met Saddam Hussein, working instead only with Iraq’s Foreign Ministry. So her last-minute sit-down with Saddam came out of the blue, no time for nuanced instructions from Washington.

Saddam walked in wearing a sidearm, an omen, one could say. When Glaspie asked why, he raised an eyebrow, but handed his pistol to an aide. He then started in on a meandering 10-minute soliloquy about Kuwait’s “economic war” on Iraq.

When he paused to take a breath, Glaspie replied, “We have no opinion on . . . your border disagreement with Kuwait. But,” she continued, “we can see that you have deployed massive troops in the south. When this happens in the context of what you said, . . . that the measures taken by the U.A.E. and Kuwait are . . . military aggression against Iraq, then it would be reasonable for me to be concerned. And for this reason, I . . . ask you, in the spirit of friendship, not confrontation, your intentions.”

Saddam replied, “We want to find a just solution, . . . but we want others to know that our patience is running out, . . . their actions are harming even the milk our children drink, and the pensions of the widow who lost her husband in the war . . . .” He went on, “Not all wars use weapons and we regard this as a kind of war, a military action, against us. . . . I said to [President Mubarak of Egypt], . . . ‘[A]ssure the Kuwaitis that we are not going to do anything until we meet with them. . . . [W]hen we see there is hope, then nothing will happen. But if there is no hope, then . . . Iraq will not accept death, even though wisdom is above everything else.’” Translation: If push comes to shove, we will go to the war with Kuwait, and the U.S. too, even if it would be a very dumb thing to do.

Glaspie then asked: “What solution would be acceptable?” Saddam: “If we are forced to choose between keeping half of the Shatt (al Arab waterway) and the whole of Iraq (including Kuwait), then we will give up all of the Shatt to . . . keep the whole of Iraq in the shape we wish it to be.”

Glaspie’s response: “Secretary (of State) Baker has directed me to emphasize . . . that the Kuwait boundary issue is not associated with America.” Whatever that means.

Next, on July 31, 1990, in a hearing before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Chair Lee Hamilton (D. Ind.), who was a straight talker, asked Assistant Secretary of State John H. Kelly:

Hamilton: “If Iraq, for example, charged across the border into Kuwait, for whatever reason, what would be our position [on] the use of U.S. forces?”

Kelly: “That, Mr. Chairman, is a hypothetical . . . I can’t get into. Suffice it to say, we would be extremely concerned, but I can’t get into . . . what-ifs.” In the gallery, Iraq’s embassy staff were taking notes.

Meanwhile, the Kuwaitis had finally agreed to abide by OPEC quotas and had been persuaded by Egypt’s President Mubarak to make financial concessions to Iraq. But by this time Saddam had, with his inflammatory rhetoric, painted himself into a corner. Any compromise, any backing down, would be perceived in Bagdad as weakness, and he knew how that could turn out for him.

August 2. Two days after Kelly’s testimony and exactly one week after Glaspie met with Saddam, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Glaspie was widely criticized for giving Saddam a “green light.” Not really, but neither did she put up a stop sign, nor did Tutwiler, Kelly, Secretary of State James Baker or anyone else in the Bush administration. Mixed messages at best.

Sven weeks later, September 19, Kelly was back in front of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and Chairman Hamilton took him to task. “You left the impression that it was the policy of the United States not to come to the defense of Kuwait. That was the impression this committee member had, that was the impression I think most committee members had as a result of your testimony, and it is not surprising that is the impression that the press has as well. . . .” And Saddam too.

Joe Wilson, Deputy Chief of Mission in Bagdad from 1988 to 1991, argued later that Glaspie was “scapegoated,” that her “no position on the Iraq–Kuwait border” was nothing more or less than long-standing U.S. policy, and that any diplomat in her shoes would have said exactly the same thing.

Wilson asked a reporter: “What would you have had her say? If you invade Kuwait, we will bring the B-52’s over and bomb you back into the stone age. No diplomat would ever say anything like that.”

No, Joe, as a diplomat we wouldn’t put it quite that way. But given Saddam’s threatening rhetoric, his 30,000 troops on Kuwait’s border and the CIA warning that an invasion was “likely,” Glaspie could have said, should have said, “We have no position on the merits of your boundary or oil disputes with Kuwait, but we see you are massing troops on the border. So there is no mistake, let me speak plainly. If you were to attack Kuwait, my government and the international community would not stand back and watch. It is our position that your border disputes with Kuwait must not be resolved by force of arms, but diplomatically, and on that front we would be happy to do all we can to help.”

But Glaspie didn’t say that. And when we don’t say what we mean, dance around the point and resort to pat answers, then someone like Saddam Hussein, whom we supported after he invaded Iran because of a border dispute, will hear exactly what he wants to hear, that we will not object to him invading Kuwait over a border dispute. As the warden memorably said to Cool Hand Luke, “What we’ve got here, people, is a failure to communicate.”

_______________________________________________________________________

Afternote: In April 1991, Glaspie testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. She claimed that, in the July 25 meeting, she had “repeatedly warned [Saddam] against using force to settle his disputes with Kuwait,” but this is not reflected in the Iraqi transcript, and the State Department never released its version.

Asked how Saddam could have interpreted her comments as implying that the U.S. would not defend Kuwait, Glaspie replied, “We foolishly did not realize he was stupid.” Clearly not stupid, but understandably confused, if not misled. And that’s not just on Glaspie.

Glaspie never returned to Iraq and never again was given an appointment requiring Senate confirmation. She was first assigned to a low-profile position on the State Department’s U.N. staff, and then as U.S. Counsel General in Cape Town, South Africa, until retiring in 2002. From up and coming front-runner to fall-girl.

________________________________________________________________________

One final thought: Was all this just bureaucratic bumbling, or could it have been intentional? Ramsey Clark, former U.S. Attorney General, who headed the Gulf War International War Crimes Tribunal, concluded that the Bush administration enticed Saddam into invading Iraq, just as Jimmy Carter and Zbigniew Brzezinski induced the Soviets to invade Afghanistan in 1980.

Clark argues, “It was not Iraq but powerful forces in the United States that wanted a new war in the Middle East, the Pentagon to maintain its huge budget, the military-industrial complex, with its dependence on Middle East arms sales and domestic defense contracts, oil companies who wanted more control over the price of crude (oil), . . . [so that the U.S.] could establish a permanent military presence . . . and control of its oil resources.”

In fact, on August 23, 1990, Saddam offered to pull Iraqi forces out of Kuwait in return for control of the Rumaila oil field, more direct access to the Persian Gulf via the lease or purchase of Bubiyan and Warba from Kuwait, the lifting of sanctions and resolution of its grievances with Kuwait and OPEC about oil prices, in short, a place to start negotiations, but dismissed out of hand by the Bush administration.

On January 2, 1991, Saddam softened his position, asking only that the U.S. not attack Iraq’s forces as they withdrew from Kuwait, go forward with resolution of Palestinian/Israeli issues, and ban all nuclear weapons in the region, but his offer to negotiate was again rejected by the Bush administration and ignored by U.S. media, as if it never happened.

William Blum, a former State Department officer, summed it up, “The U.S. military . . . would have its massive show of power, . . . and no signals from Iraq or any peacenik [like Ramsey Clark] would be allowed to spoil it.”

________________________________________________________________________

Recommended:

John Bulloch and Harvey Morris, Saddam’s War: The Origins of the Kuwait Crisis and the International Response (1991)

Elaine Sciolino, The Outlaw State: Saddam Hussein’s Quest for Power and the Gulf Crisis, (1991)

Theodore H. Draper, The Gulf War Reconsidered, (New York Times Review of Books, January 16, 1992)

________________________________________________________________________

Next: 1991 Persian Gulf War – Desert Shield

Recent Comments