Post 15. Desert Storm – The Air War

[Featured Image: Reuters]

On the January 15, 1991 deadline for unconditional withdrawal, Saddam’s forces in Kuwait were still dug in, and two days later, January 17, the U.S., with its coalition partners in tow, went to war against Iraq.

One hour before the air assault was to begin, James Baker got a call from the new Soviet Foreign Minister, Alexander Bessmertnykh, who relayed a personal request from Mikhail Gorbachev to delay the bombing and give him time to make one last appeal to Bagdad. Baker said, “Well, no, there’s too much that’s been put on the train, Sasha, we can’t call this off now.”

It was the beginning of an unrelenting 39-day strategic bombing campaign, dubbed Operation Instant Thunder, in which U.S., British, French and Saudi warplanes would launch 120,000 sorties and drop 88,500 tons of bombs. War is always good for business; the Dow Jones Index gained 114 points the first day.

Tomahawk cruise missiles launched from warships in the Gulf, and “smart bombs” delivered by F-117 Nighthawk stealth bombers, wiped out Iraq’s command and control and integrated air defense systems, including Baghdad’s, which had stronger air defenses than Eastern Europe during the Cold War.

Iraqi fighters made a few token sorties, but were either shot down or fled, 122 of them to, of all places, Iran, where the Ayatollah refused, no surprise, to return them until 2014.

In all, coalition forces destroyed more than 400 Iraqi planes without a single air combat loss. Iraqi surface-to-air missiles did take out 26 coalition planes, killing 24 pilots and crew, 14 of them in an AC 130 Spectre gunship on January 31.

Schwarzkopf later told reporters, “I thought, back when the war began, that we’d have more aircraft losses by now, more air-to-air combat, . . . but instead it’s been like a beagle chasing rabbits, . . . all pleasant surprises.” In fact, within the first 10 days, the coalition had button-down air superiority, able to destroy ground targets relentlessly and with impunity.

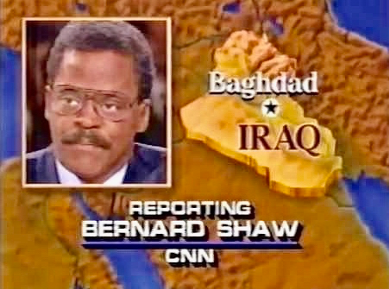

Desert Storm dominated the nightly news, ratings went through the roof. Network anchors, CBS’s Dan Rather, NBC’s Tom Brokaw and ABC’s Peter Jennings, played dual roles, as much patriotic cheerleaders as news anchors.

But Ted Turner’s CNN took center stage, with Peter Arnett, Bernard Shaw and John Holliman reporting live from their suite at Baghdad’s Rashid Hotel, thanks to producer Robert Winner patiently cozying up to Iraqi authorities, who after the bombing started let CNN stay when they kicked everyone else out.

Desert Storm was dubbed the “video game” war, as prime time viewers watched camera-equipped “smart bombs” locked in on targets all the way to impact, including the infamous cruise missile that zipped down a Bagdad street and turned left at the traffic light. Whatever reservations Americans had early on, many became rabid patriots once the shooting started.

Saddam’s response? Scud missile attacks, not on Coalition forces, but on Israel. On January 18, the day after the bombing campaign started, eight Scuds hit residential neighborhoods in Tel Aviv and Haifa, wounding seven, another on January 23 killed three. Before it was over, there were 30 more, and U.S.-supplied Patriot anti-missile missiles more miss than hit.

Saddam wanted Israel to retaliate, because he knew that the Syrians, Egyptians, even the Saudis, who loathed Israel even more than they feared Iraq, would likely pull out of the coalition, it would be the end of its “Arab face.” Saudi Deputy Prime Minister Sultan bin Abdulaziz al Saud said flatly that he would not permit Israel to defend his country.

But the Israelis never turn the other cheek. True to form, Defense Minister Moshe Arens told Dick Cheney, “We’re going to attack [Iraq], move your airplanes.” But Cheney put Arens off with one excuse after another, and by promising to intensify the hunt for Scud launchers, President Bush was able to convince Prime Minister Yitzak Shamir to stand down.

Scuds were notoriously inaccurate – Norman Schwarzkopf said that when a siren sounded in Riyadh, he “didn’t even bother to get out of the shower” – and much more a terror threat than an effective military weapon. The big fear, for coalition forces and Israel alike, is that Saddam would arm his Scuds with poison gas, as he had done with artillery shells in Iraq’s war with Iran.

[Pascal Guyot / Getty]

But James Baker had made clear to Tariq Aziz in Geneva that chemical attacks were a “red line,” that the U.S. would respond with nuclear weapons – and Israel too – and go after Saddam personally, regime change in Bagdad. Saddam would risk much, but not that, chemical weapons were off the table.

At a January 30 press briefing, General Norman Schwarzkopf got in on the act, showing a video clip of a truck crossing a bridge just seconds before it was destroyed by a laser-guided bomb, and calling the driver “the luckiest man in Iraq,” eliciting uproarious laughter from reporters in the room.

Now a more sobering perspective. Although the number of Iraqi civilians killed directly by coalition bombs was surprisingly low, 3,664 is the oft-cited number, 408 were incinerated on February 13 when two F-117 stealth bombers dropped 2,000-pound bombs on an air raid shelter in Bagdad’s al-Amiriyah neighborhood.

Article 51, Protection of Civilian Population, of Protocol I to the 1977 revisions of the 1949 Geneva Convention, prohibits attacks on non-combatant civilians, including “indiscriminate attacks . . . that may . . . cause incidental loss of civilian life . . . excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.”

Article 57, Precautions in Attack, requires that “Those who plan or decide upon an attack shall . . . do everything feasible to verify that the objectives to be attacked are [not] civilians . . . [and] refrain from [launching] any attack . . . expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life. . . . Effective advance warning shall be given of attacks which may affect the civilian population, unless circumstances do not permit.”

Pentagon officials claimed al-Amiriyah was an “alternative command post,” but later admitted knowing it had been a civil defense shelter during the Iraq-Iran War and might still be. It is fair to say that killing 408 civilians was beyond excessive relative to the very marginal military utility of obliterating what might be an alternative command post 400 miles from Kuwait. With no warning, none. What part of the Geneva Convention did coalition target planners not understand. Did they even read it? For Radiohead’s 6th album, Hail to the Thief, Thom Yorke wrote “I Will” about al-Amiriyah.

However horrific and unnecessary the al-Amiriyah tragedy was, 408 was only a tiny fraction of total non-combatant deaths, estimated at 110,000 including 23,000 women and 74,000 children, caused by the destruction of the electric power grid and ensuing collapse of Iraq’s water, sanitation and public health systems.

In the lead-up to the bombing campaign, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) had identified, in addition to the Iraqi forces on the ground in Kuwait, 700 strategic targets, most in a swath running southeast from Baghdad to Basra between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, starting with airfields, air defense installations, command and control centers, nuclear, biological and chemical weapons facilities, Scud missile sites, ports, railroads, bridges and oil refineries.

But also on the target list, 20 electric power plants, plus transmission lines, transformers, switching yards, hydroelectric dams and pumping stations, which the coalition hit with Tomahawk cruise missiles and laser-guided BGU-10 bombs, annihilating Iraq’s electric power grid. One week into the bombing campaign, as one target planner put it, “not an electron was flowing.” All but two of Iraq’s generating plants were destroyed or severely damaged, and months afterwards its electrical generating capacity, for a heavily urbanized population of 18 million, was less than 25% of pre-war 9,500 MW.

Totally dependent on electric power, Iraq’s water purification and sewage treatment plants stopped functioning. Tap water was unfit to drink. Raw sewage backed up into homes and streets and discharged untreated into the Tigris River. Only a handful of Iraq’s 131 hospitals and 851 community health centers were functioning, and those that were lacked reliable electricity for operating theatres and laboratories.

Three months later, an inspection team from the Harvard School of Public Health found “epidemic levels” of cholera, typhoid and dysentery, along with widespread acute malnutrition, and predicted that “at least 170,000 children under five years of age would die in the coming year from the delayed effects” of the bombing. Two renowned child psychologists found the children of Iraq to be “the most traumatized children of war ever.” A United Nations inspection report called conditions in Iraq “near apocalyptic.”

Mikhail Gorbachev saw this coming. “I pictured the destruction of the country . . . . I told President Bush, ‘You know, George, you should think about not how to get in this war, but how to get out of it.’ If the United Nations saw that we were not only trying to stop the aggression but ruin the Iraqi state, . . . then we were exceeding their mandate.” And, he could have added, committing war crimes.

Article 54 of Protocol 1 expressly prohibits the destruction of “objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, such as [food], . . . crops, livestock, drinking water installations . . . works, for the specific purpose of denying them . . . to the civilian population . . . whatever the motive, . . . [and] in no event shall actions . . . be taken which may be expected to leave the civilian population with such inadequate food or water as to cause its starvation.”

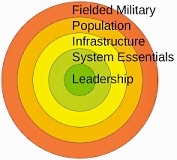

But Col. John A. Warden III, who as head of the Pentagon’s Project Checkmate devised the Desert Storm bombing campaign based on his own Five Rings theory of strategic attack – infrastructure being the third ring – believed that “by destroying Iraq’s electrical grid, you have imposed a long-term problem on the leadership that it has to deal with. . . . [We] can say, ‘Saddam, when you agree to do these things, we will allow people to come in and fix your electricity,’ it gives us long-term leverage.”

Air Force officers also argued that Iraqi civilians were complicit in Saddam’s invasion to Kuwait. “The definition of innocents gets to be a little bit unclear,” said one senior officer, oblivious to the ruthlessness with which Saddam dealt with real and suspected opponents of his regime, “They do live there, and ultimately the people have some control over what goes on in their country.” So they have to pay with malnutrition and disease? This is called “collective punishment,” an egregious breach of international law.

Lt. Gen. Charles A. Horner, who had overall command of the air campaign, quipped that a “side benefit” of the strategic bombing was the psychological effect on ordinary Iraqi citizens of “having their lights go out.” Amusing in the moment perhaps, but the real life consequences were not.

[John Rice / AP]

In the Jan/Feb 1995 edition of Foreign Affairs, French diplomat Eric Rouleau summed it up: “The Iraqi people, who were not consulted about the invasion, have paid the price for their government’s madness. . . . Iraqis understood the legitimacy of a military action to drive their army from Kuwait, but they have had difficulty comprehending the Allied rationale for using air power to systematically destroy or cripple Iraqi infrastructure and industry: electric power stations (92 percent of installed capacity destroyed), refineries (80 percent of production capacity), petrochemical complexes, telecommunications centers (including 135 telephone networks), bridges (more than 100), roads, highways, railroads, hundreds of locomotives and boxcars full of goods, radio and television broadcasting stations, cement plants, and factories producing aluminum, textiles, electric cables, and medical supplies.”

This what happens when a commander in chief cedes strategic decisions to his generals. As Baker said later: “We knew that politicians had dictated the [conduct of the Vietnam War], that . . . the military had never been able to fight the war they thought they needed to fight to win it, and he [President Bush] was determined to let the military call the shots . . . about how [Desert Storm] was conducted, about when it ended and all the rest.”

Which was just fine with Schwarzkopf and his target planners working out of the “Black Hole” in the basement of the Royal Saudi Air Force headquarters and creating the Air Tasking Order (ATO), what bombs get dropped, where and when. Once the war started, the ATO was etched in stone and as a practical matter the President and the Pentagon were out of the loop.

Certainly, the lesson of Vietnam is that civilians should not micro-manage a war, as Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy and their “best and brightest” brain trust did. But it is the responsibility of the President, not generals, to answer the seminal questions: What do we want to do accomplish with military force and, just as critically, are there any limits on what we will or will not do?

Was it, per U.N. Resolution 660, to compel Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait? Oust Saddam Hussein? Destroy Iraq’s industrial base, its electrical grid, regardless of the short- and long-term devastation for millions of ordinary Iraqi people? Punish them for not deposing Saddam?

Bush abdicated his responsibility, never answered those questions, so his generals did they were trained to do, annihilate the enemy with all of the resources at their command. To be clear, Schwarzkopf, Horner and their staff did not intentionally target Iraqi civilians, for the most part they tried to avoid bombing neighborhoods, but destroying Iraq’s infrastructure had even more lethal consequences.

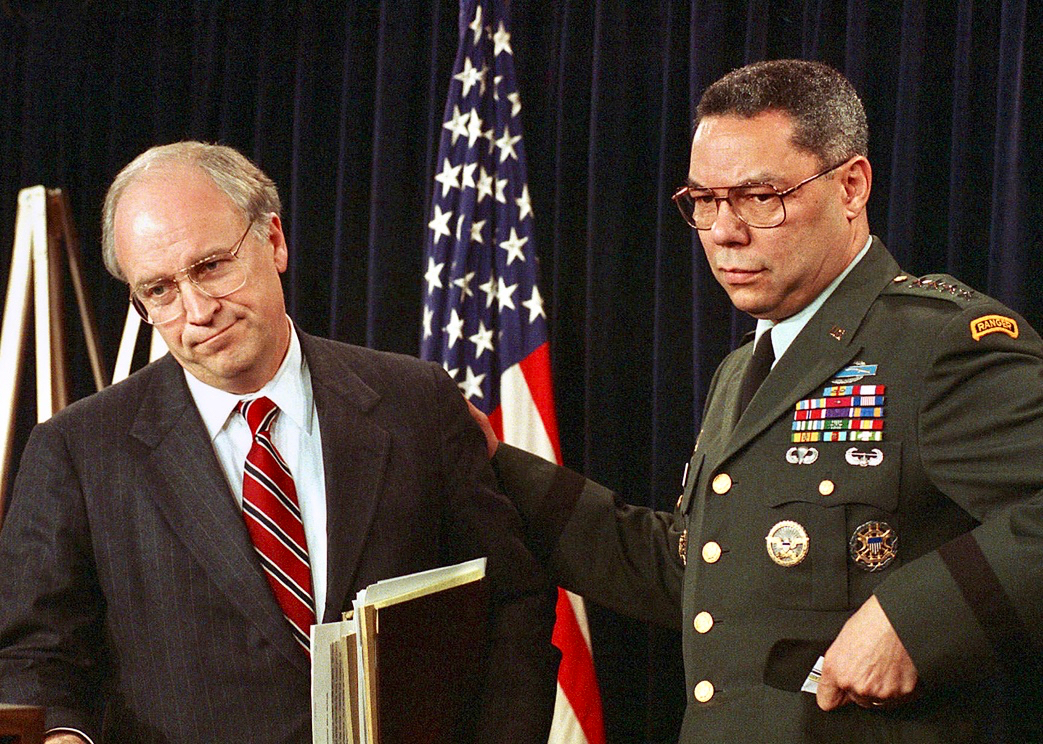

Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, for one, had no second thoughts – he never does. “Once war begins, . . . your number one obligation is to accomplish your mission and to do it at the lowest possible cost in terms of American lives. . . . My own personal view is that there are a large number of Americans who came home from the war . . . who would not have come home at all if we had not hit the strategic targets and hit them hard.”

Cheney begs the question, which is not whether the coalition’s strategic bombing of military targets was justified, even if it resulted in “collateral damage,” i.e., some civilian deaths, rather whether the wholesale destruction of Iraq’s civilian infrastructure was necessary on military grounds. It was not.

In World War II, it took the Allies more than five years to defeat Nazi Germany, and so destroying its industry and infrastructure was not just warranted, but imperative. Not so in the First Gulf War. CENTCOM’S war plan, only 30 days of bombing followed by a lightning ground assault, assumed that Iraq would not have the time or means to regenerate its military forces, e.g., manufacturing more tanks, more artillery shells, and that it would be a very short war indeed.

So destroying Iraq’s civilian infrastructure, particularly its electrical power grid, and with it Iraq’s water filtration and sewage treatment plants, would make no difference in the outcome, much less reduce the number of American casualties. From a military standpoint, taking out the grid was nothing less than indiscriminate, reckless, “piling on.” And, yes, we are held to a higher standard.

But what about Saddam himself? In mid-September 1990, General Michael J. Dugan, appointed just two months earlier as Air Force Chief of Staff, told the Washington Post that “the only effective option for driving Iraqi forces out of Kuwait” was heavy bombing of Baghdad to “decapitate” the top Iraqi leadership, starting with Saddam, his family and senior commanders.

Three days later, September 18, Cheney fired Dugan, saying in an hastily called press conference that he had shown “poor judgment at a very sensitive time,” and that it was “inappropriate for U.S. officials to talk about targeting specific foreign officials,” a potential violation of Executive Order 11905, banning political assassinations, issued by President Gerald R. Ford in February 1976. “Sorry, General Dugan, you can’t say out loud what we’re all thinking.”

General Horner admitted as much in a press briefing, “I don‘t think any of us would have lost any sleep if Saddam Hussein had been killed. . . . As a matter of policy, we were not trying to assassinate him, but we dropped bombs on every place that he should have been at work. Now . . . we‘re getting kind of fancy with words, but . . . that‘s the truth of the matter.”

And in fact, very early on in the bombing campaign, coalition bombers pulverized Ba’ath party headquarters, and when an intelligence report put Saddam in a bunker outside Bagdad, they obliterated that too, but he was canny and disciplined enough to stay in the suburbs, moving every night from one house to the next.

At the same time, Bush and Cheney fretted that without Saddam to keep the lid on the pressure cooker of Sunnis, Shi’a and Kurds all in the same pot, Iraq would collapse into anarchy, as indeed it did when the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 and Saddam ended up hiding in a hole in the ground north of Baghdad.

This ambivalence about getting rid of Saddam would persist, first as a pivotal factor in Bush Senior deciding not to go all the way to Baghdad after routing Iraqi forces in Desert Storm, next in at first encouraging and then abandoning Shi’a and Kurdish rebels in their uprisings against Saddam at the end of the Gulf war, and in Bush Junior’s rash decision, based on cherry-picked intelligence about non-existent weapons of mass destruction, to invade Iraq in 2003, where regime change was indeed the prime objective.

________________________________________________________________________

References:

Dirk Adriaensens, Water Under Siege in Iraq. US/UK Military Forces Risk Committing War Crimes by Depriving Civilians of Safe Water (2003)

Human Rights Watch, Needless Deaths in the Gulf War: Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War (1191)

Next: Desert Storm – The Ground War

Recent Comments